Written by Admin and published on https://www.conservationhandbooks.com/.

For local authorities needing to remove a tree from a public space or for homes suffering from structural damage, tree felling may be the most suitable remedial action.

Essentially, tree felling is the action of cutting down a tree to prevent the spread of disease and improve safety in the area. If not carried out correctly, tree felling can be very dangerous – as such, this type of work must be carried out by a tree care specialist who will plan the task meticulously, taking into account any potential hazards or risks.

So, why do trees sometimes need to be felled?

Table of Contents

Why fell trees?

Tree felling is a positive management technique which increases the health and diversity of trees and their associated wildlife within woods. It should be carried out as part of a management plan based on scientific research of the effects caused, and should be appropriate to the species concerned.

Felling trees in the name of conservation is often misunderstood. Not surprising when we consider that an estimated 19 million trees were blown down in the storms of 1987 and 1989 and more than 30 million trees have been lost to Dutch Elm disease. But felling is an essential part of woodland ecology and management. Non-indigenous trees and shrubs, for example, may need to be removed to retain the character of a woodland.

How woodland develops

In most of the UK, if all agriculture and land management ceased and nature was allowed to take over, woodland would be the end result. It is the UK’s ‘climax’ vegetation, able to renew itself indefinitely with saplings springing up into the spaces left by the death of large mature trees.

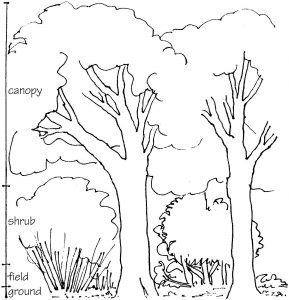

The woodland would grow, mature and change over hundreds and thousands of years reacting to climate and soil conditions. The forest canopy would be dominated by associations of relatively few large species such as oak, ash, beech, and lime (and probably sycamore). However, there would be a great diversity of flora and fauna existing within the woodland ecosystem particularly in glades and woodland edges, areas of wetland, permanent grassland and thickets.

Woodland history

Wildwood once covered most of Britain but has been modified and managed by humans since the first clearances for settlement and agriculture by Mesolithic and Neolithic man some 6,000 years ago.

For at least 2,000 years, until this century, woodlands and their products have formed a vital part of the local society and economy.

Woodland now covers 13% of the UK’s land surface, compared to a 37% average for EU countries. However, it is estimated that only 552,000ha in the UK is ancient woodland sites (around 2.3% of land area) and of this 223,000ha is planted with non-native species (referred to as planted ancient woodland sites (PAWS)) – The State of the UK’s Forests, Woods and Trees, Woodland Trust. More than a quarter of the tree cover is Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis), introduced from the west coast of North America.

Types of woodland

Woodlands can cover less than 10 hectares or more than 350,000 hectares. Most are on farmland where the landowner may not realise its commercial and conservation value. Woods have been neglected because they are no longer needed.

Primary or ancient woodland

An area of land that has been under uninterrupted woodland cover, without dramatic change to the constituent tree types. Mainly woods which have been managed by coppicing.

Secondary woodland

An area of land which has been cleared at some stage but allowed to regenerate naturally. New secondary woodland lacks a full range of native species. Old secondary woodland can have almost as diverse a range of species as ancient woodland but lacks ‘indicator’ tree and plant species such as wild service tree, small-leaved lime, woodland hawthorn (Crataegus laevigata) and oxlip which cannot colonise readily into new areas.

Plantation woodland

The modern practice of forestry has resulted in many conifer plantations usually containing single, or a very limited number of, species of the same age. All coniferous species in the UK, apart from Scots pine, yew and juniper have been introduced. However, some beech, oak and chestnut plantations from the 18th century still thrive.

Parkland and urban trees

These are sometimes the remnants of original woodland cover, existing as single mature trees and perhaps showing signs of management such as pollarding. Otherwise they tend to be new plantings, often of exotic species.

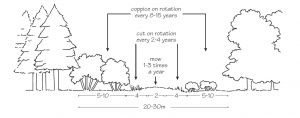

Coppicing

The traditional woodland management system of coppicing creates a structure which varies from open glade through brambles and scrub on newly exposed areas, dense thickets of competing young saplings growing around fallen tree trunks, closed shady canopies of mature forest to ancient stag-headed trees. Woods are divided into compartments and trees and shrubs are cut on a rotation based on the number of years it takes for the ‘underwood’ to reach its desired size. This gives rise to an irregular patchwork of panels of trees of different ages, offering wildlife a wide range of habitats.

Felling trees in this way does not kill a wood. Bradfield Woods in Suffolk, first recorded in 1252, though probably old even then, has been cut down at least 70 times in its history of coppice management.

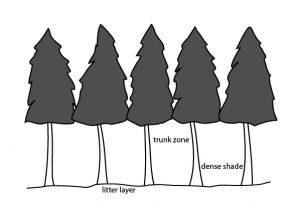

In direct contrast, most plantation forestry has no variety of structure or species. It casts dense shade to suppress ground vegetation and is often clear-felled when mature. Exotic species do not regenerate and the area has to be planted again. Conifers that have been planted within old coppiced woods may have to be felled to return the wood to traditional management.

Conifer woodland structure

Thinning

Thinning is the removal of a proportion of trees in a wood. It is usually associated with commercial forestry – providing an intermediate crop and leaving more growing space for the remaining trees. Most planted forests begin with 1,000 to 2,500 trees per hectare but end up with 70 to 350.

Thinning in secondary woodlands is needed where there is little age range among the trees. Such woods often spring from colonisation of bare ground, tending to form a high dense canopy of close growing trees. Thinning will allow light in to help shrub and ground flora growth and allow the best trees to spread and mature.

Rides and glades

Only 2% of woodland in the UK is managed as coppice, so often the only open places within woods are rides and glades. They attract a completely different flora and fauna from the rest of the wood. Species are attracted by the open sunny conditions and interface or ‘edge’ between grassland and woodland.

The grassland may be a relict population of unimproved grassland – 95% of which has been lost from the surrounding countryside since the Second World War.

Butterflies are sun-loving insects and the majority breed only in very open rides and glades which provide warm and sunny microclimates. Most butterfly larvae feed on the low-growing herbs of the open ride, whilst many more moths breed on the tree and shrub species – particularly sallow and aspen – of the shrubby margins.

Shrubby margins can be attractive to several species of breeding migrant birds such as garden and willow warblers and nightingale. Low tangled vegetation is a favourite nest site of the chiffchaff. Wrens will breed if heaps of brushwood are left after cutting. Sparrowhawks will hunt up and down the rides and green woodpeckers may be attracted to feed on ants.

Rabbits are commonly found deep inside woodlands and may be dependent on grassy rides and glades as feeding sites. Bats also use rides for hunting attracted by the rich insect life.

Indigenous species

The term ‘indigenous’ refers to species that are of natural origin. Introduced, exotic, or non-indigenous trees have been brought to this country by man.

As the ice from the last glaciation retreated, about 13,000 years ago, trees moved northwards. The first to colonise our tundra were pioneering species such as birch, aspen and willow. These were followed by pine and hazel, alder and oak, lime and elm, then holly, ash, beech, hornbeam and maple. The later arrivals were either species from warmer climates or poor colonisers.

Non-indigenous species

During the 18th and 19th centuries, exotic trees, which were ‘discovered’ in the new world, were planted in many large ornamental gardens. In the 19th century hardy, fast growing species, mainly conifers, began to be planted for economic forestry.

Felling and uprooting of non-indigenous tree and shrub species in semi-natural woodlands is often necessary to retain the woodland’s character. These species generally have the habit of being able to spread quickly, dominating the understorey and ground vegetation – suppressing a more diverse native flora and regenerating seedlings.

Rhododendron

The rhododendron family is native to central Asia and has been planted in this country both for the beauty of its blossom and its value as game cover. Although rhododendron cannot tolerate lime-rich soils it seems to thrive everywhere else. The plant develops an ever-spreading thicket of tough evergreen leaves, smothering all other growth so that no field or ground layer of vegetation can survive.

Laurel

This shrub was planted for similar reasons to the rhododendron and has similar effects. The leaves decay slowly to the detriment of soil humus.

Snowberry

Snowberry fruits

Snowberry was planted for game cover. Although birds and insects do feed on the small white berries, the plant can spread quickly and shut out a more diverse flora.

Sycamore

Sycamore grows in shade, is little affected by pollution and disperses great quantities of fertile seed annually. It can be a self-sown constituent of many secondary woods and encroach ancient woodlands when they are disturbed or opened up. Indigenous plant diversity can be reduced as sycamore becomes the dominant species. It often has to be clear felled to eradicate it from sensitive sites.

However, sycamore is a valuable hardwood timber tree and is often specified in new lowland plantings. It only supports a small diversity of insect life but can be more important to feeding birds than beech, ash and hazel because of its high biomass. It will grow in exposed, upland sites where other hardwoods won’t survive.

Original post https://www.megainteresting.com/nature/article/how-trees-survive-and-thrive-after-forest-fires-741579248339.